If the audience doesn’t understand what’s happening, they stop caring. Right?

Yet one of my favorite pieces of fiction, the 2000 anime mini-series FLCL, manages to be incredibly engaging despite being nearly incomprehensible on a first watch. Why doesn’t the viewer bounce out? How was this erratic, absurd, stylish thing even made?

Having worked with interactive narrative for over a decade, I’ve found that my curiosity for how “FLCL” was made has only grown stronger.

Through extensive research into interviews, production materials, and anime creation in general, this article deconstructs the creative process of the cult classic. At the end, I’ll share my reflections, drawing from my own experience in the creative industry.

My Next Girl Will Be Nothing Like My Ex-girl 🔗

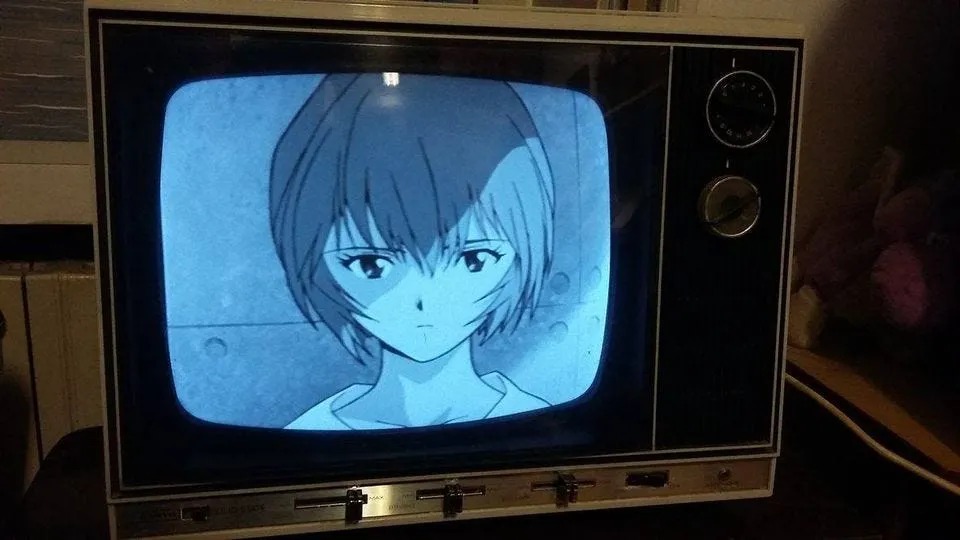

FLCL lives in the shadow of Neon Genesis Evangelion, the studio’s (GAINAX) pioneering series that aired in 1995 and concluded with the 1997 film The End of Evangelion.

Speaking to mynavi.jp in 2010, Tsurumaki stated that in the year following Evangelion’s completion, he juggled numerous ideas for his directorial debut but struggled to solidify any one concept. After taking a break to assist with the production of His and Her Circumstances (1998), he tried again, resolving to be less of a perfectionist, focusing more on the things he loved and less on the things that brought stress.¹

Evangelion(TV) photo credit: twitter @telewaifus

In the book FLCLick Noise, 2010 Tsurumaki recalls that at this time GAINAX underwent significant changes in the animation staff, impairing the studio’s ability to execute highly realistic animation. But unlike Evangelion, where the directors imposed strict style-guides on the animators, Tsurumaki wanted FLCL to be an animation playground.²

The intention was for FLCL to be the opposite of Evangelion’s somber tone, to be outrageous and wacky. Speaking at the Otokon Convention in 2001, Tsurumaki remarked:

With Evangelion, there was this feeling that you had better be smart to understand it, or even just to work on it. With FLCL I want to say that it’s okay to feel stupid.

This sentiment not only encapsulates the experience of viewing FLCL, but it also speaks to its themes: growth, what it means to be an adult, and taking chances to learn new things — even if you look silly doing it.

From Scribbles to a Pitch 🔗

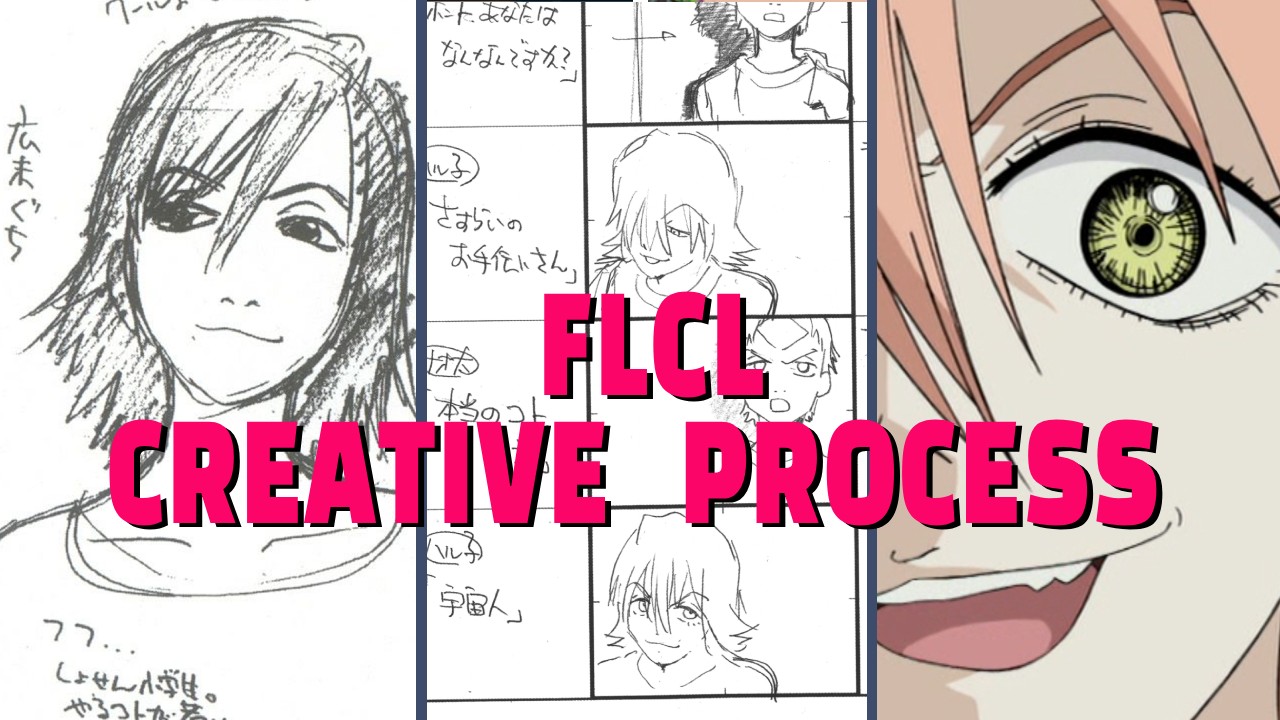

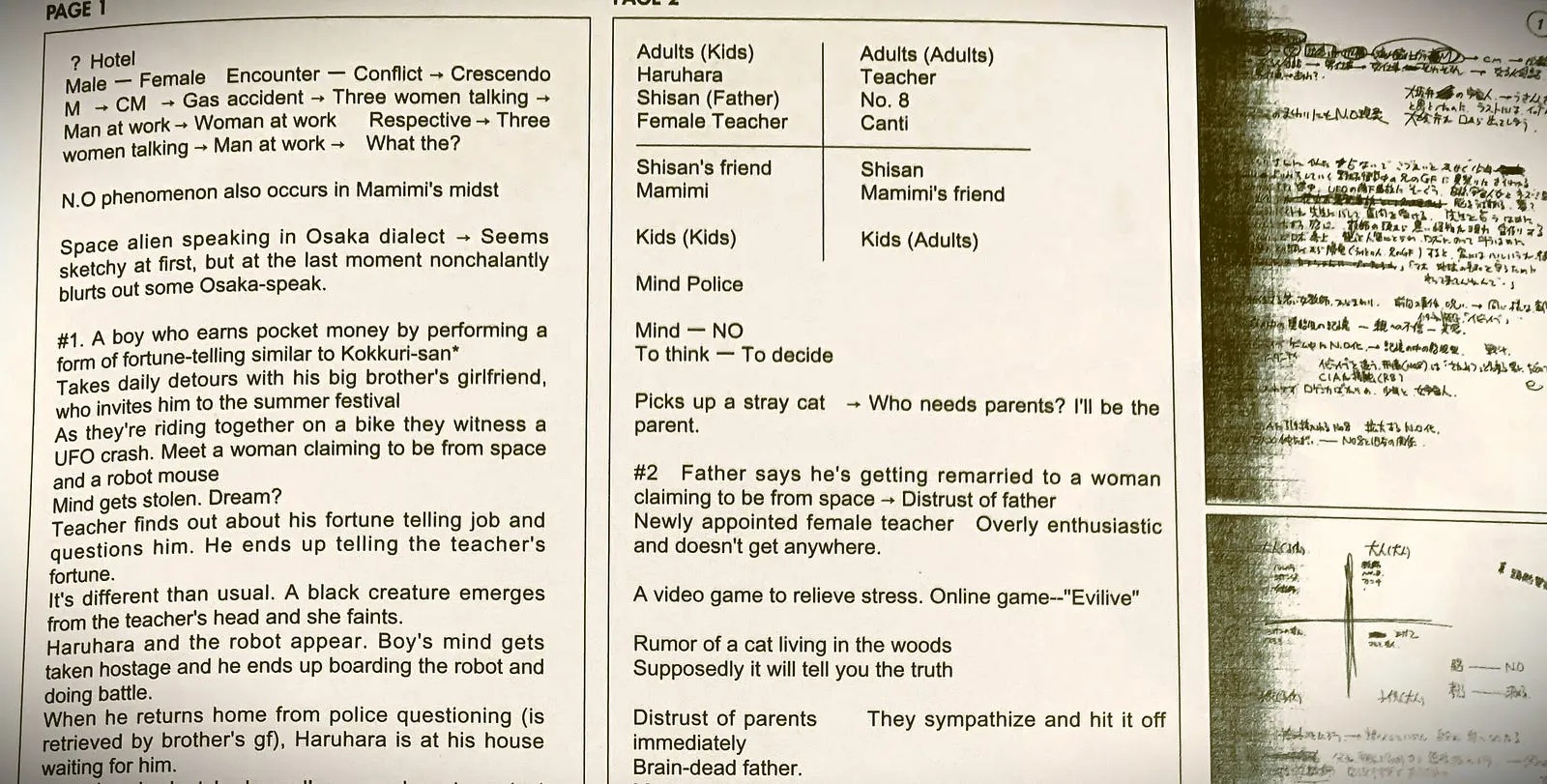

In the 2019 book FLCL Archives, we can see the early scribbles by Tsurumaki in what would become FLCL. These notes already capture the theme, some of the characters, and the setting.

FLCL Archives, Initial notes, undated

The later, more refined outlines are signed by FLCL’s screenplay writer, Yoji Enokido. Staff comments from the DVD commentary³, FLCL Noise⁴, and in the afterword of the 2007 novelization⁵ make it clear that Enokido played a major role in developing the show’s characters, their interpersonal dynamics, and the snappy, metaphor-heavy dialogue.

For Enokido, like any good writer, it’s all about tying everything back to the theme, regardless of how absurd it gets.

It doesn’t matter if the content is completely absurd. Rather, it is this surface absurdity with which we compete for. However, there is only one thing that must not be a lie — the creator’s wish to express the theme.

— Yoji Enokido FLCL, Ultimate Edition Booklet (2007)

FLCL Archives (2019), notes dated 4/24/1999

My impression is that Tsurumaki had been thinking about the theme of maturity for some time before pre-production. The earliest scribbles include a graph where the characters are plotted by their maturity and age.

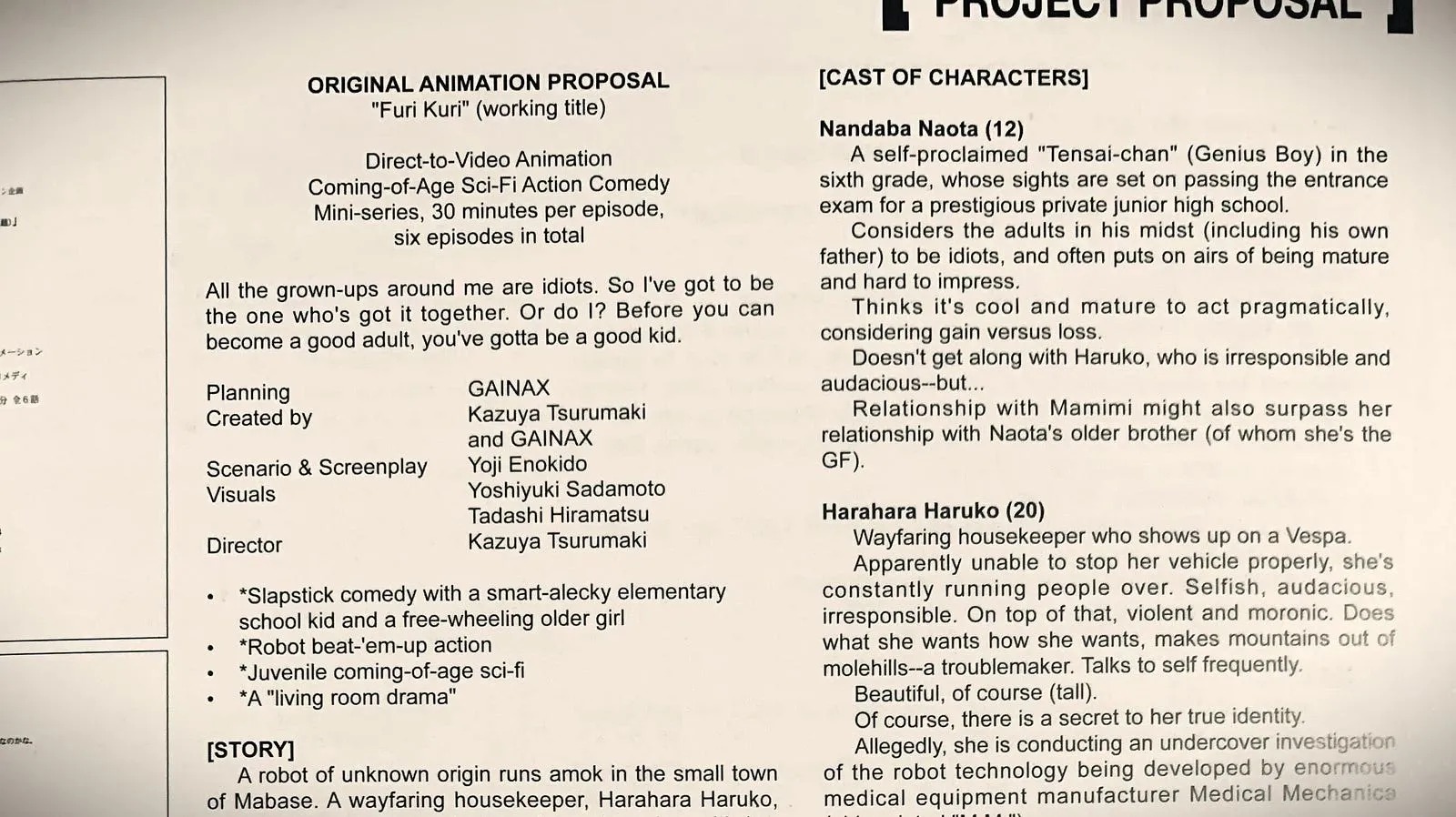

Reviewing GAINAX’s production timeline⁶ and the dates noted in FLCL Archives⁷, we can estimate that it took 2–3 months from the early draft until they had a refined pitch. It was going to be a six-episode Coming-of-Age story featuring comedy and action.

For the structure, it’s a surprisingly standard boy-meets-girl but the team pushes the tropes to absurdity. For example, the format traditionally features a cute scene where the couple-to-be bumps into each other. What’s the FLCL version?

“Well, what if he got run over? Or, what if he got hit with the guitar?” Things like that, make it full of nonsense.

— Tsurumaki, DVD Commentary, eps 1 (2002)

Early Casting and a Lucky Break! 🔗

An early decision that would play a major role in defining the show’s spirit was the casting of stage actress Mayumi Shintani to voice Haruko — the selfish, violent, possibly alien character that wreaks havoc on the protagonist’s life.

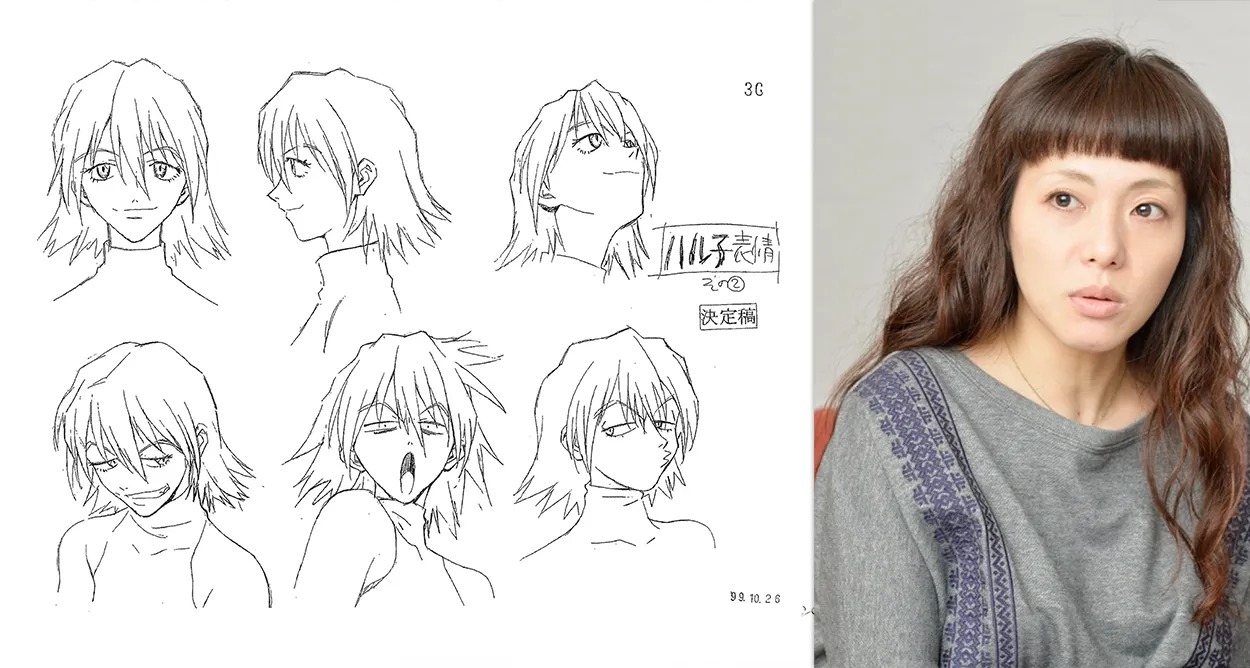

Character designer Sadamoto noted that he was struggling with Haruko’s design for a long time, but when he heard Ms. Shintani was cast, it finally came together.

With a voice like that I couldn’t help but imagine a mean face, and as a result Haruko’s face turned out like, well, how it did (laughs) .

— Sadamoto, FLCLick Noise, Episode 1

Haruko Model Sheet by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto & Mayumi Shintani (right)

The music was also picked in pre-production. Tsurumaki stated that he lacked confidence in directing composers. To him, a great score is when a well-known, great track is laid on top of the animation.

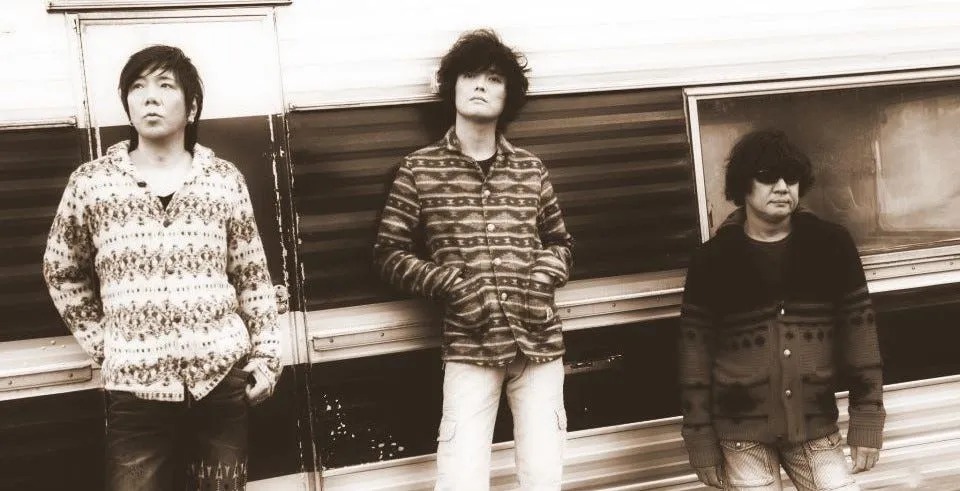

It was this line of thinking that led him to approach The Pillows, his favorite band, not to commission them for new songs, but to use their back catalog for the score.

So if, by any chance, The Pillows said, “Don’t use any of the existing songs, order a custom soundtrack from us,” I would have been in a lot of trouble, I think.

— Tsurumaki, FLCLick Noise, Episode 1

The Pillows in 2011 | Left to right: Yoshiaki Manabe, Sawao Yamanaka, Shinichiro Sato.

Making this choice in pre-production significantly skewed the tonality of the show. Instead of animating and then placing music to fit, the animation was set to the music (or with the music in mind), similar to music-video production.

Shaking the Habitual 🔗

In traditional anime production, once an episode’s script is completed, it’s handed over to the Episode Director and Storyboard Artist, who draw a storyboard (a sequence of sketches to map out the scenes planned for the episode). Once drawn, the storyboard is returned, reviewed, and corrected by the Series Director. This was the formal structure GAINAX had been operating under.

In FLCLick Noise, Tsurumaki alludes to the fact that the formality of this structure was loosened by letting the Storyboard Artist be part of the early development of the script.

Once I had written the core plot, I asked Imaishi to come up with ideas, and then I used what he came up with in the script.

More radically, Tsurumaki would shape the script to the style of the animator responsible for the episode — even when it went against his personal preference — as long as it stayed in line with the theme, he let them go all-out.

I wanted to play to Imaishi’s strengths… (a) poetic and subdued tone… might have been my personal preference… but it wouldn’t have had the strength to make people still love it even after ten years .

— Tsurumaki, FLCLick Noise, Episode 5

Left: Animator, Tadashi Hiramatsu. Right: Animator, Hiroyuki Imaishi

This would generate wildly different animation styles between scenes and episodes depending on which animator was responsible. The mixing of styles also created interesting contrasts, such as Hiramatsu’s skill in conveying intimacy with Imaishi’s wild Kanada style for slapstick comedy.

We wanted to convey the message that “this anime is chaotic and anything goes.” We wanted it to be just “animation” without any restrictions on expression typical of the genre.

— Tsurumaki, FLCLick Noise, Episode 1

In FLCLick Noise, we learn that there were several instances where the Storyboard Artists would improvise additional sequences that weren’t mentioned in the script at all⁸. These off-script sequences could be wacky or fun, but they could also misdirect the viewer trying to make sense of the plot. In a 2002 Pulp — The Manga Magazine interview, Tsurumaki commented:

I wanted to have it more in the style of a Japanese TV commercial or promotional video — it’s short, but it’s dense-packed. That’s the look I was aiming for.

Wait, what about the plot? Her lover is a bird? 🔗

With the script getting filled with sub-culture jokes and the animation team going more off-model and off-script. Clear communication of plot and events became less of a priority and was in fact purposely deprioritized.

In a 2010 interview for mynavi.jp, Tsurumaki notes that he told writer Enokido to skip beats in the dialogue flow and omit everything they didn’t think was important, including elements of the Sci-Fi setting.¹⁰

Atomsk, the pirate king and desire of Haruko | Concept by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto

That meant a lot of backstory, character motivations and world building only flash by in a split second between densely packed gags and visual references.

Tsurumaki maintains in several interviews that making a layered show was a conscious choice. In FLCLick Noise, he states that he didn’t want to disrespect the DVD buyers by selling them something they would understand at first viewing.

But it’s worth noting that there are several acknowledgments from the director in FLCLick Noise¹³ and the DVD commentary¹⁴ where he apologizes for some of the narrative leaps and recognizes that it’s not very clear.

Production! Finally, some rigor and rules. Right? 🔗

GAINAX worked in collaboration with Production I.G. during production. This is where storyboards are turned into video. Even here, where anime production is at its most streamlined, a few stylistic twists still slipped in.

Layout -> Final Animation (Layout Artist unknown)

In a traditional anime production, each episode has an assigned Animation Director who distributes a number of cuts among the Key Animators. They will draw the essential frames, which are then passed back to the Animation Director for a consistency check and any necessary corrections.¹⁵ ¹⁶

As recounted by Tsurumaki in FLCL Noise¹⁷, Shinya Ohira, a renowned senior from Ghibli, was under contract with Production I.G at the time and got assigned a few cuts for a scene on the porch in episode 2. However, when the senior returned his keyframes, they looked distinctly unlike anything else; it was hard to even tell who the characters were.

The work was supposed to be cleaned up, but a younger Animation Director felt intimidated by the senior and delayed making corrections. With the deadline looming and the young director procrastinating, they simply decided to leave it, add some subtitles with names, and call it a day. After all, it’s FLCL.

Shinya Ohira scene looks like nothing else in the show

What can creators learn from FLCL’s process 🔗

Tsurumaki puts a lot of faith in the individual contributors and breaks production hierarchies. In order to even get there you have to be in a team that has a lot of confidence and respect for each other. A traditional production pyramid structure helps decisions get made, and too many cooks in the kitchen is almost always detrimental.

Loosening established work structures can have additional conflict. Tsurumaki mentions struggles with staff more accustomed to the traditional structure. In FLCLick Noise, character designer Sadamoto notes some reluctance to the heavy modification of his designs¹⁵ ¹⁶, and I can imagine Writer Enokido similarly saw a lot of his storytelling reduced.

By loosening some areas, it can help to have rigor in others. First, for all its wackiness, FLCL follows a very familiar boy-meets-girl format. That familiar spine lets everyone know what needs to happen when, while still giving them a box to be creative within.

Second, using pre-production to reach out to talents outside your own field requires bravery but can create a guiding light. The Pillows music and Yoshiyuki Sadamoto pick for Haruko helped the team find direction and designs, and likely, making the outcome far more distinctive than a production that brings in talent for music and voice over last.

For me, it’s genuinely refreshing to learn that FLCL was born from a desire to “not be a perfectionist,” but simply to work on the things that make you happy. Tsurumaki loves baseball and rock music, so the story is full of both.

Finally, whether the plot ended up so heavily obfuscated by accident or design, I find that FLCL (unlike Evangelion) is inviting. It draws me in to explore instead of dragging me through a symbolism exam set up for failure.

Why is that?

I think it comes down to the original intention: “It’s ok to be dumb! Now look at all this fun nonsense we made!”

Music videos are often nonsense, but if we enjoy the song, it demands our attention to review over and over again. FLCL captures that energy, and if you’re into it, the narrative depth underneath becomes an enticing puzzle to unravel.

An eariler version of this article was posted on Medium (2023)

[1] 10 years since then… (2010). Mynavi.jp, p.1,

[2] FLCLick Noise — Episode 5 (2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[3] FLCL: Volume 1 [DVD] (2002). Episode 1, 00:08:21

[4] FLCLick Noise — Episode 4(2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[5] Afterword by Hiroki Sato. “FLCL Volume 1" TokyoPop 2008

[6] “GIANAX,” MyAnimeList, accessed on 8/10/2023

[7] GAINAX, “The FLCL Archives”, Udon Entertainment, 2019. — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[8] FLCLick Noise — Episode 4(2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[9]Kazuya TSURUMAKI, Q&A session, Otokon Convention. Baltimore. 2001

[10] 10 years since then… (2010). Mynavi.jp, p.1,

[11] 10 years since then… (2010). Mynavi.jp, p.1

[12] Kazuya TSURUMAKI, Q&A session, Otokon Convention. Baltimore. 2001

[13] FLCLick Noise — Prologue (2010). - Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[14] FLCL: Volume 2[DVD] (2002). Episode 4, 00:12:22

[15] Trash Taste Highlights, “Professional Animator Explains How Anime is Made”, Youtube, published on 2021/02/14

[16] Washi Blog, Anime Production — Detailed Guide to How Anime is Made and the Talent Behind it! published on 2011/01/18

[17] FLCLick Noise — Episode 2(2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[18]FLCLick Noise — Episode 1(2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)

[19]FLCLick Noise — Episode 5(2010). — Simulacra Realities. (2023)